For decades, America had a chokehold on how art’s success was measured. It was where the early days of blues flourished, influencing Elvis and Little Richard, who in turn would influence The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

From there, a British invasion would take place, and the sensibilities of either side of the pond would clash, creating the blueprint of what we now consider contemporary artistic success. The glamorous flamboyance of American performance, combined with the gritty storytelling of British voices, would essentially define rock and roll.

Until the 1990s, when transatlantic trends would take a break from one another, inside the white picket fences of America, grunge thrived while Cool Britannia gave way to all things British on domestic shores. Colloquialisms, mod cuts and parkas were all encouraged, and softly feigned American accents while singing were no longer in vogue.

As such, the idea of “breaking America” was less important. Particularly to Oasis, who prided themselves on their uncompromising attitude, never cowering to the expectations of others, especially if they wore a suit and worked for a label. Because they knew, the very reason American audiences couldn’t quite understand their brilliance was the same reason why British fans held them so dear. Whatever you thought of the band, they were resolutely real.

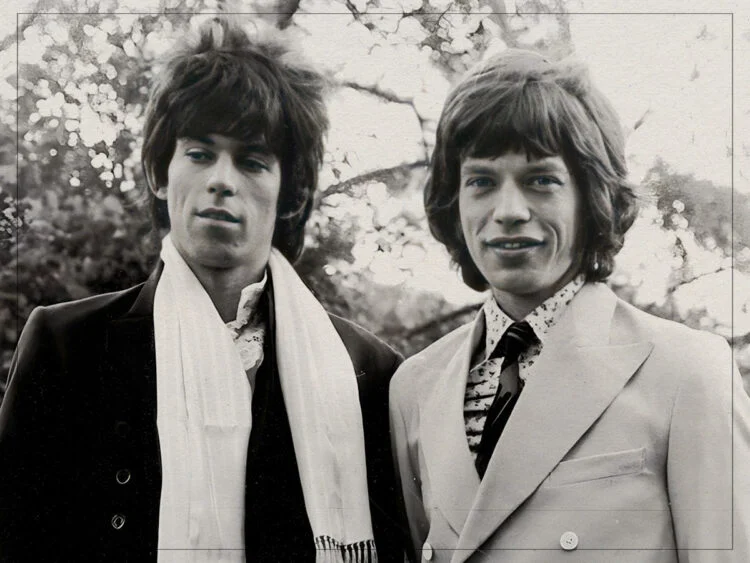

Because there is an element of contrivance required to become a world-dominating band, which is an ability to contort your performance to the needs of different audiences that Oasis just weren’t willing to do. And maybe American fans took exception to that, for there had been plenty of British bands from years gone by that had done that. Perhaps none more than The Rolling Stones.

Mick Jagger was the master conductor for a band ready-made to charm American audiences and deeply understood the floridity required for maintaining transatlantic success. So when the torch was passed to the Gallagher brothers a few decades later, it’s safe to say he wasn’t impressed with how they carried it.

When asked about the performance style, he said, “Well, that’s what they do, they don’t move—that doesn’t mean to say they don’t connect—they do connect sometimes, sometimes they’re not always good ways.”

He continued: “What was that famous story when they were in New York and they didn’t think the New York audience was loud enough, and they said something like ‘You’re rubbish’ or something, ‘New York, you’re a load of crap’ or something like that, which is not what you do anywhere really, especially in New York.”

Maybe in the violent days of New York’s mid-1970s, slandering their atmosphere may not have been the play. But by the time the ’90s rolled around, Oasis were the figureheads of a more bulletproof brand of British rock. They felt as though they had nothing to prove, as they were slowly learning success wasn’t exclusive to America.

But moreover, brilliant art is in its authenticity. While Oasis took parts of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Smiths and cultivated the blueprint of their sound, anything more would have simply been a replica. And in replicas, there is never greatness.