It almost felt like musical fate that Led Zeppelin‘s debut album came out in 1969. Just as The Beatles switched off the lights at Abbey Road for the final time, Jimmy Page was plugging his guitar in and striking the first note of what would become their decade.

Of course, the 1970s, in general, gave way to an exciting time when more than just one band could dominate the airwaves. But Zeppelin wasted no time staking their claim to the throne with two albums in 1969 that were the envy of every outfit trying to find their sound. But in their case, timing really was everything, for these albums weren’t the product of overnight success.

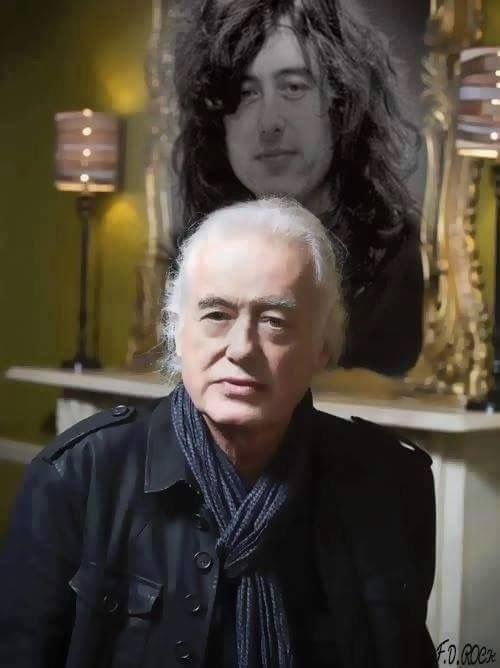

No, the individual members of what we came to be Led Zeppelin were tirelessly toiling at the grindstone in the 1960s. Jimmy Page, in particular, became a mainstay in what is well known as a legendary underground London blues scene, cutting his teeth with a string of other soon-to-be stars in what seemed like a carousel of bands.

Carter-Lewis & the Southerners, Mike Hurst & the Method, Mickey Finn & the Blue Men and The Yardbirds all had Page at some point in the 1960s. He lurked in the dark corners of the moody clubs, carving out blues riffs that were painstakingly necessary for the greatness that would later follow.

So, where most mere mortals have just one sliding doors moment professionally, Page had several. By this point, he had already seen a future as an iconic session musician, as well as gifting riffs to artists, which opened the door as a sort of Bernie Taupin-esque songwriter, if you will. But Page patiently waited, allowing those doors of opportunity to pass him by, before eventually stepping through the right one—the one of Led Zeppelin.

But that didn’t stop him from scratching the itch of those alternative avenues. Page had more than enough riffs to go around, and so his brilliance can be heard outside the realms of Led Zeppelin’s greatness. In fact, David Bowie had no shame about not only using a riff he showed him but also regularly ripping it off when out of ideas.

He recalled a time when the guitarist was but a mere whippersnapper, making himself known in the London blues scene, transfixing audiences with his solos. But in his youth came naivety, and he willingly gave his riffs to Bowie to use however he wished.

“He just got a fuzz box, and he used that for the solo,” he said. “He was wildly excited about it, and he was quite generous that day, and he said, ‘Look, I’ve got this riff but I’m not using it for anything, so why don’t you learn it and see if you can do anything with it?’ So I had his riff, and I’ve used it ever since! [laughs]. It’s never let me down.”

Bowie rather oddly used that in his experimental drum and bass song, ‘Dead Man Walking’, which I’m sure a 20-something blues head in Page wouldn’t have expected. But were he to feel slightly miffed that his idea had been turned into an electronic Frankenstein’s monster, he could always turn his listeners to some other projects he had worked on.

In the mid-1960s, his name was quietly responsible for a string of hits. He provided the string-bending riff for The Nashville Teens’ ‘Tobacco Road’, the 12-string on The Kinks’ ‘I’m a Lover (Not a Fighter)’ and lead guitar for The Rolling Stones’ ‘Heart of Stone’.

While all three of those experiences were undoubtedly formative for Page, it was a track he laid down for Nico that remains one of his all-time favourites. He provided the sole acoustic guitar track for her single ‘The Last Mile’, in 1965. This came years before her encounters with Warhol and The Velvet Underground, but he knew the talent he was in front of, as he noted, “It was such a thrill to have done that single with Nico, having written something with Andrew Oldham and going in there and just doing ‘The Last Mile’, which was really cool.”

When she later went on to define New York’s art-pop scene, her profound influence on his work remained ever clear. He said, “Everyone talks about The Velvet Underground, but at the time, people did not go to see them, and I found that odd. I loved The Velvet Underground.”